Professor Shing Yip Lee

Director Simon F S Li Marine Science Laboratory (CUHK)

Mangroves are an incredibly effective tool against climate change by storing carbon. However, in the past 30 years, the mangrove habitat has been generally regarded as an exporter of materials, including carbon, to the coastal ocean, among other services such as providing stopover sites or nursery areas for migratory birds, fish and mammals. Their carbon storage role, however, has not been seriously considered. Professor S.Y. Joe Lee, Director of Simon F.S. Li Marine Science Laboratory of CUHK and a mangrove specialist who has been researching coastal wetlands for more than three decades. His recent work with his postdoctoral fellow Dr. X. Ouyang found that the conversion factor conventionally used for assessing mangroves carbon stock was wrong and confirmed that mangroves and other marine wetlands stored 23% more carbon from the atmosphere than previously estimated, which exemplifies the astonishing impact of “Blue Carbon” in mitigating climate change.

Professor Lee measuring sediment CO2 flux in a mangrove plantation in Malaysia.

Professor Lee and his research team have combined data from past studies in different countries and new field measurements of sediments in tidal wetlands. Through comparison and analysis as well as inclusion of previously neglected components (e.g. dead wood), the team revealed that carbon stocks in mangrove forests reach 3.7-6.3 Pg (one Pg = 1015 g or one billion metric tonnes), which suggests a previous underestimate of 23%.

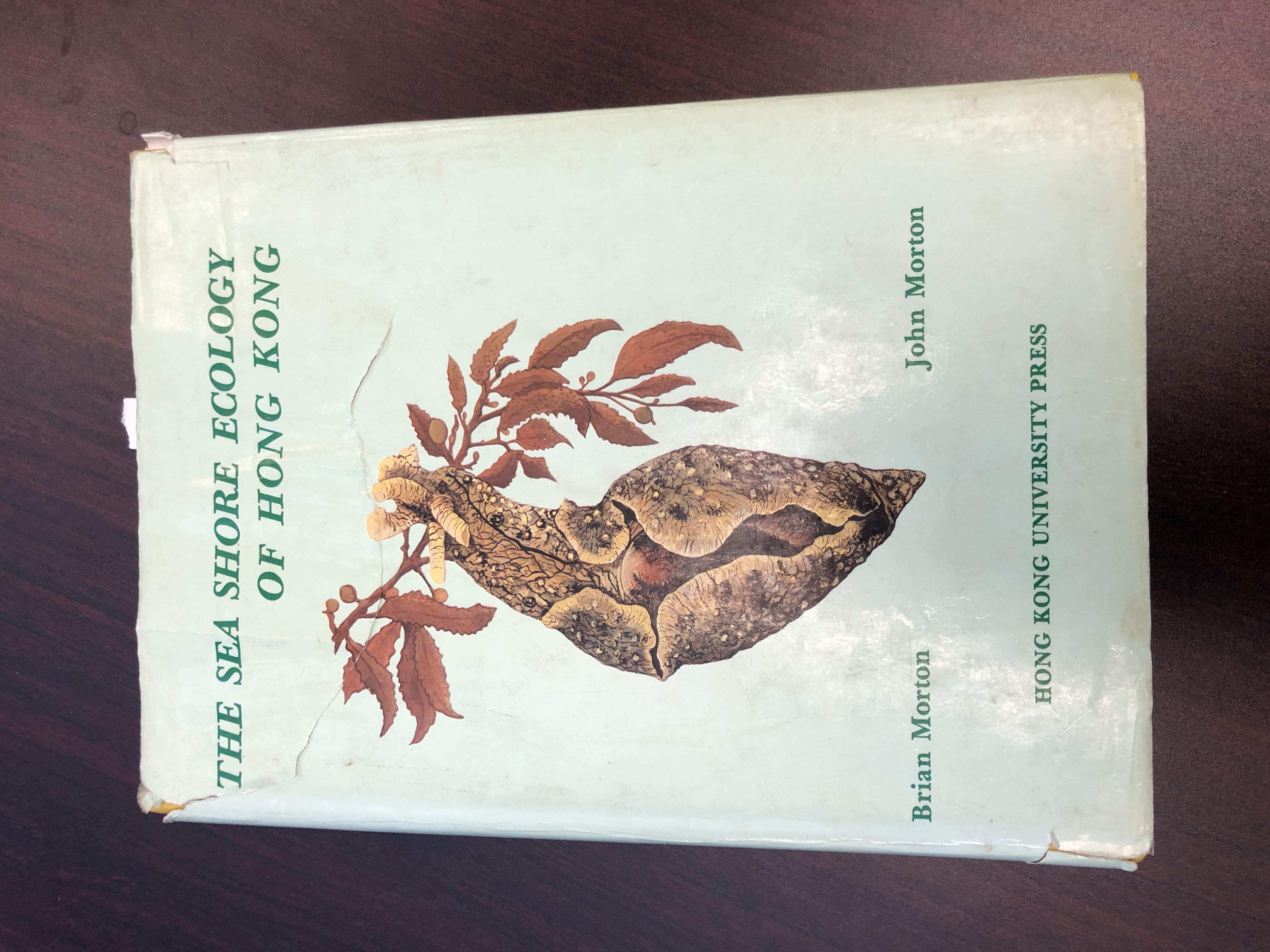

Prof. Lee revisited the book “The sea shore ecology of Hong Kong” written by Marine Ecologist Professor Brian Morton 30 years ago, and praised him for his profound influence on the ecological conservation of Hong Kong.

The capacity for carbon storage in the mangrove ecosystem is high. When mangrove leaves fall, they are usually covered by sediment. Mangrove sediments have low oxygen concentration, slowing the breakdown of organic matter and thus, boosting carbon storage.

However, some organisms in the mangroves can accelerate carbon emissions. For example, there is a high density of crab burrows in tropical mangroves. These burrows will become conduits, allowing oxygen to enter the deep soil and carbon dioxide to be discharged through the pipes. Interestingly, Professor Lee observed some crab species in the mangrove forests of Hong Kong and Australia that harvest freshly fallen leaves. “They usually hide in the burrows, and as soon as they sense a leaf has fallen they quickly retrieve it before returning underground. When the leaves are consumed and assimilated by the crabs, they contribute to CO2 emissions.” Therefore, processes mediated by the animals are very important to the carbon cycle and are the object of Professor Lee’s research.

Prof. Lee observed some crab species in the mangrove forests of Hong Kong and Australia that harvest freshly fallen leaves.

Mangroves are remarkably tough. With their roots submerged in water, mangrove trees thrive in hot, muddy, salty conditions, but they still support diverse fauna (including snakes, insects, rats, and ants – they are still part of the biodiversity). Professor Lee admitted that mangrove forests may at first sight not as inviting as blue-water coral reefs, and perhaps less attractive to young people involved in research, particularly if that involves working for a long time in soaring temperatures. Professor Lee likened mangroves to “Pi Dan”(century eggs) – “they may not win an award for instant visual appeal and the first bite for 'novices'' could be challenging, but if you get used to eating them you may eventually find them delicious.” Professor Lee laughed. “Similarly, if you are willing to spend time studying mangroves, you will find them to be very special.” He added, “Trees that grow in the sea? They adapt to challenging conditions and have developed amazing physiological structures, shapes and ways of reproduction. Mangroves are survivors.”

The research titled “Improved estimates on global carbon stock and carbon pools in tidal wetlands” was published in the scientific journal Nature Communications in January last year.