Can Confucianism Help Rebuild Hong Kong?

Award-winning professor argues that strong humanities programmes at universities can promote citizenship and combat generational conflict

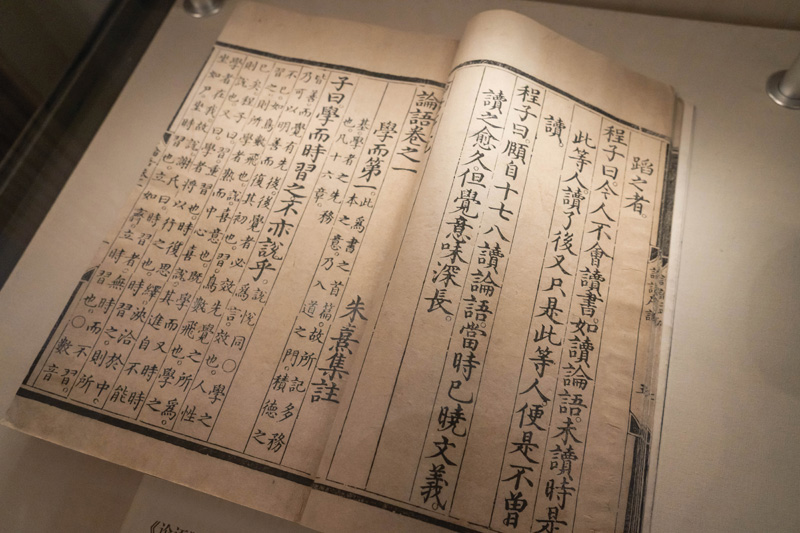

At the heart of Confucianism are qualities such as honesty, chivalry and benevolence, some principles that make it compatible with democracy.

Professor Kim Sung-moon believes that many East Asian democracies have lost sight of certain important cultural values that distinguish them from Western democracies.

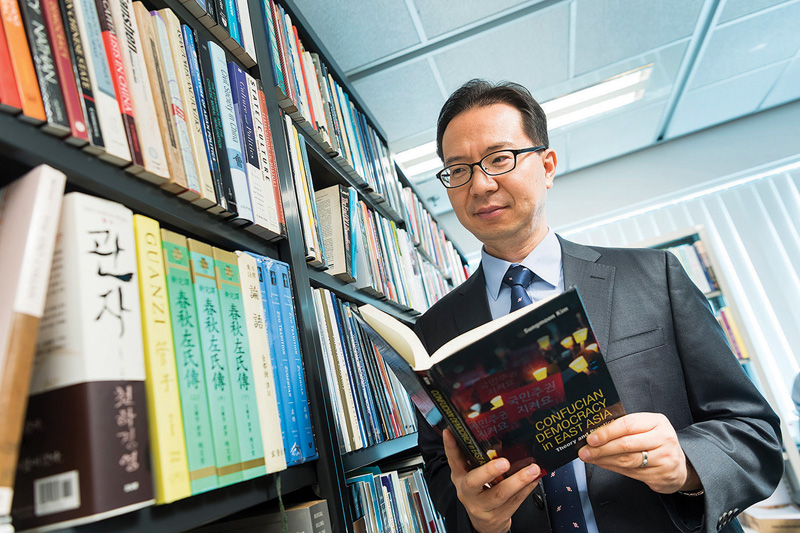

Professor KIM Sung-moon, Associate Dean (Postgraduate Studies) of CityU’s College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences (CLASS) and Professor of the Department of Public Policy, has received one of the University’s Outstanding Research Awards, and he could not be happier. Not because of any thirst for personal glory, but because he believes it will help inspire his fellow CLASS colleagues.

“I feel this award is extremely important, not just because of the recognition of my research, but for my colleagues’ morale, motivation and spirit,” says Kim, who is also Director of CityU’s Center for East Asian and Comparative Philosophy. “It is no secret that my university is known for its strong sciences, and at times it feels like those of us in the humanities and liberal arts sectors are a little bit overshadowed. But I believe I am part of an institution with great professors, teachers and students, and this award vindicates our hard work.”

Kim was recognised for his leading research on Confucian democratic theory—a subject on which he has published three books.

Growing up in South Korea, which laboured under a military dictatorship for much of the Cold War, and spending a significant amount of time studying and working in prestigious American universities have made Kim a strong champion for democracy. However, he believes that many East Asian democracies have lost sight of certain important cultural values that distinguish them from Western democracies.

Democracy is still relatively new in East Asia, which is why I’m asking the question: “What kind of democracy do we want to have?”

Professor Kim Sung-moon

“Democracy is a Western creation, but we see different kinds of democracies in the West with the Americans, British, Germans all boasting their own unique form of democracy,” Kim explains. “Democracy is still relatively new in East Asia, which is why I’m asking the question: ‘What kind of democracy do we want to have?’”

“Right now it feels like Taiwan, South Korea and even Hong Kong are kind of just trying to replicate Western democracies. But we are seeing democracies everywhere, including in the West, suffer. That is why I advocate for Confucian democracy, which moves away from the rights-based combative democracy that pits individuals against society and focuses more on finding a common goal, a brotherhood.”

So, what makes Confucian principles compatible with democracy? According to Kim, while some consider Confucianism to be a religion, many scholars argue that it is not religious at all. He believes that it is first and foremost a “constellation of values” that encourages qualities such as honesty, chivalry and benevolence. Phrases such as “respect your elders”, immediately come to mind.

“It is impossible to be a Muslim-Christian or Christian-Muslim. That is an oxymoron,” Kim explains. “But what’s great about Confucianism is that it has a capacious ability to be accommodated and harmonised with other religious doctrines and value systems. For example, it is completely possible to have Confucian-Christians or Confucian-Muslims. You can raise your children in a Christian household while also instilling Confucian principles.”

The professor believes that because many modern democracies have become extremely rights-based, individuals are increasingly pitted against society, and one another.

“I am in no way dismissing the importance of rights, but having it be the primary and sometimes sole-focus of certain political candidates has made modern democracy so polarising and individualised,” Kim says. “Confucian democracy can recreate the system to better serve our common bond and purpose.”

im points out that the cut-throat nature of many democratic systems has political parties locked in adversarial contests rather than negotiating and communicating with one another.

“Bipartisanship and party alignment is fine—you may choose a certain party based on your personality, beliefs and ideologies, and I think that’s a good thing,” he says, “but the problem with existing democracies in the East and the West is we don’t have this middle ground where we can communicate, where our differences can be bridged and we exchange ideas; that place is massively disappearing.”

“Confucians often talk about the importance of enriching the greater good. Even if we are competing against each other for power, at the end of the day we all belong to one political community. It’s not a republican constitution or democratic constitution, we all belong to one shared political community. So it is important to have that common tongue that can allow us all to have some sort of mutual frame of reference. And I believe that Confucian democracy can better provide us with that shared horizon which is rapidly vanishing in democracies everywhere.”

It is for these reasons that Kim believes now more than ever, universities in Hong Kong and around the world need strong humanities programmes to promote decent citizenship. He believes that he and his colleagues play a role not as politicians or political activists, but rather, as political theorists.

“I try to encourage my students and colleagues not to think of themselves as victims or participants amid political turmoil and chaos,” Kim reveals. “We don’t use hard, persuasive language like some local and world leaders do. Rather, I teach them to use abstract language and to look at the situation from a slightly more abstract perspective, which allows them to be more objective and less emotionally involved. Asking important questions like ‘what kind of leaders do we need?’ and ‘what kind of political system do we need to build to achieve this?’ We don’t need to praise or vilify any particular political party or figure in order to do this.”

In regards to Hong Kong, Kim believes that a Confucian democracy could help bridge the gap and quell the rift between young political activists and the government. Based on his research, he has proposed reinventing and modernising ancient Confucian practices and recruiting young “remonstrators” into the government in order to achieve this.

“Young people are fresh-minded [sic] and not so socially conservative,” Kim says. “They keep closer tabs on evolving public sentiment. Recruiting them not only helps them understand the complexity of public decision-making, but it also makes the government more accountable.”

He explains how during the protests that erupted in Hong Kong in 2019, civilised communication and negotiation between the government and the protestors was severely lacking. “The government was often critical of young political activists, speaking as if they were a detriment to effective governance. At the same time, many young people criticised the government as being just pure evil. So the question is how do we find this balance? How do we achieve both viable civic activism and effective governance?”

Kim notes that from an institutional perspective, political discourse in Hong Kong is sorely lacking when compared with East Asian counterparts like South Korea and Taiwan.

“It is our jobs as political theorists and academics to help citizens develop this language and common tongue to communicate with each other, regardless of political differences,” he says. “It will help them better understand the struggle and ask themselves ‘what are we fighting for?’ because fighting itself doesn’t make Hong Kong society any better.”

The scope and complexity of these issues, Kim says, means it is not something that can be tackled using hard-science methodology.

“There is no clear-cut cause and effect relationship; this is not something where you can just look at some facts and defer to the experts,” he says. “We are talking about people’s opinions, convictions, inspirations, conflicts and moralities so it is a very difficult case to tackle. And it becomes necessary for scholars like myself to create that shared language, that common ground, in order to truly improve Hong Kong society.”