Coronavirus: Hong Kong researchers discover masks could pollute over 54,000 Olympic pools worth of seawater

- City University lab study finds masks in ocean could take up to 1,000 years to decompose

- Researcher warns residents to ‘properly dispose’ of facial coverings to prevent microplastic pollution

Discarded surgical masks which fall into the sea could be releasing microplastics as they degrade, polluting an amount of water equal to 54,800 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

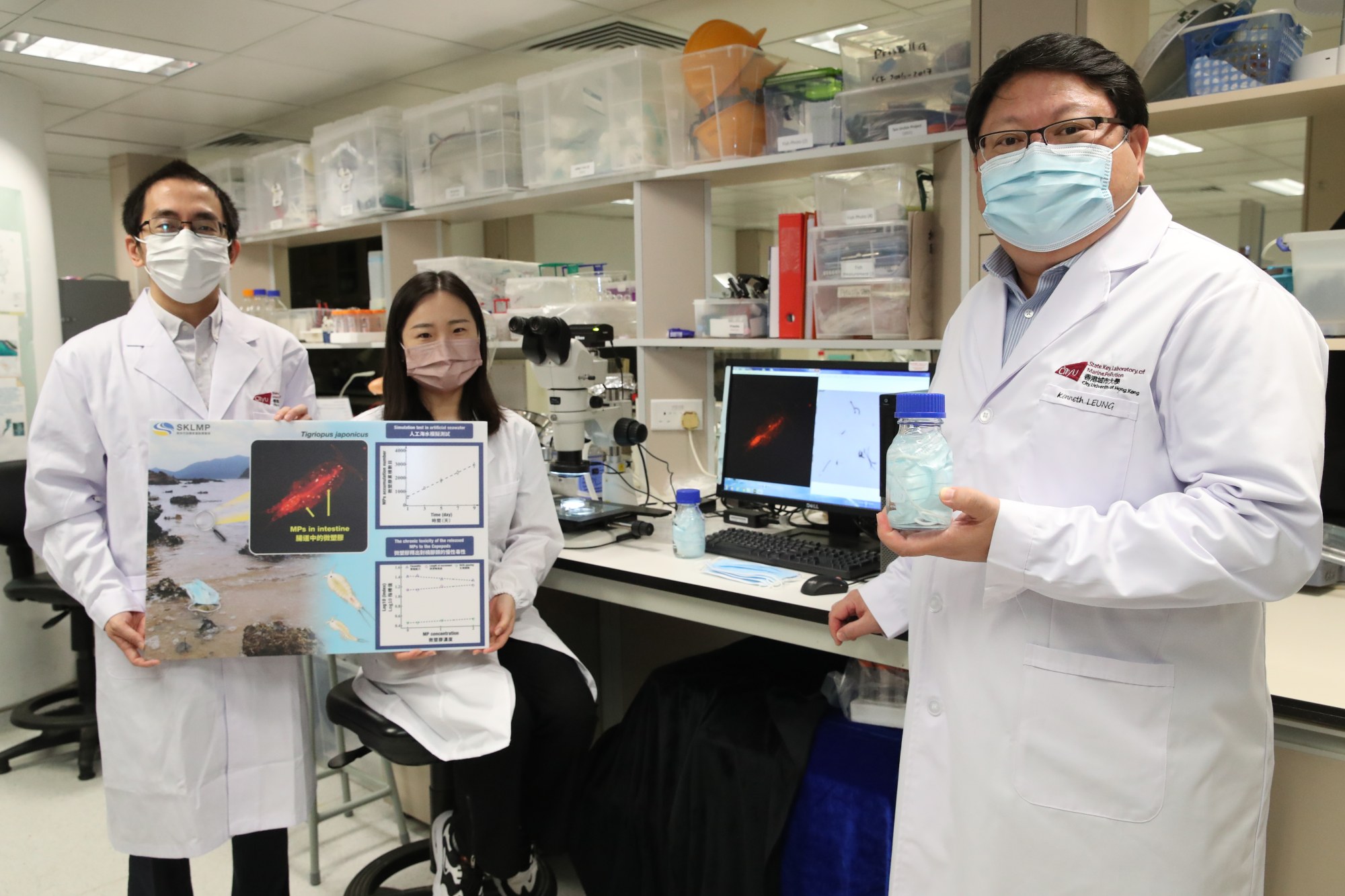

Dr He Yuhe at City University’s State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution made the discovery after spotting discarded masks at local beaches, which have seen an influx of local visitors looking for weekend haunts amid the coronavirus pandemic.

“The Covid-19 pandemic is still ongoing, and naturally if people are wearing surgical masks, then people are also dropping them,” He said.

“We really urge residents to be alert when they are out in the countryside and properly dispose of their used surgical masks to prevent them from being swept into the sea by wind or rain,” he added.

Surgical masks have become a necessity to prevent the spread of Covid-19, with an estimated 129 billion used worldwide each month in 2020.

As the masks are made from woven plastic fibres, any discarded face coverings could take anywhere from 100 to 1,000 years to fully decompose.

The United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines microplastics as any type of plastic fragment less than 5mm in length.

Once in the sea, the ocean currents and ultraviolet rays from the sun break masks down into tiny fragments or fibres. He was able to replicate the movement of waves in a lab by placing them in bottles of man-made seawater and shaking them.

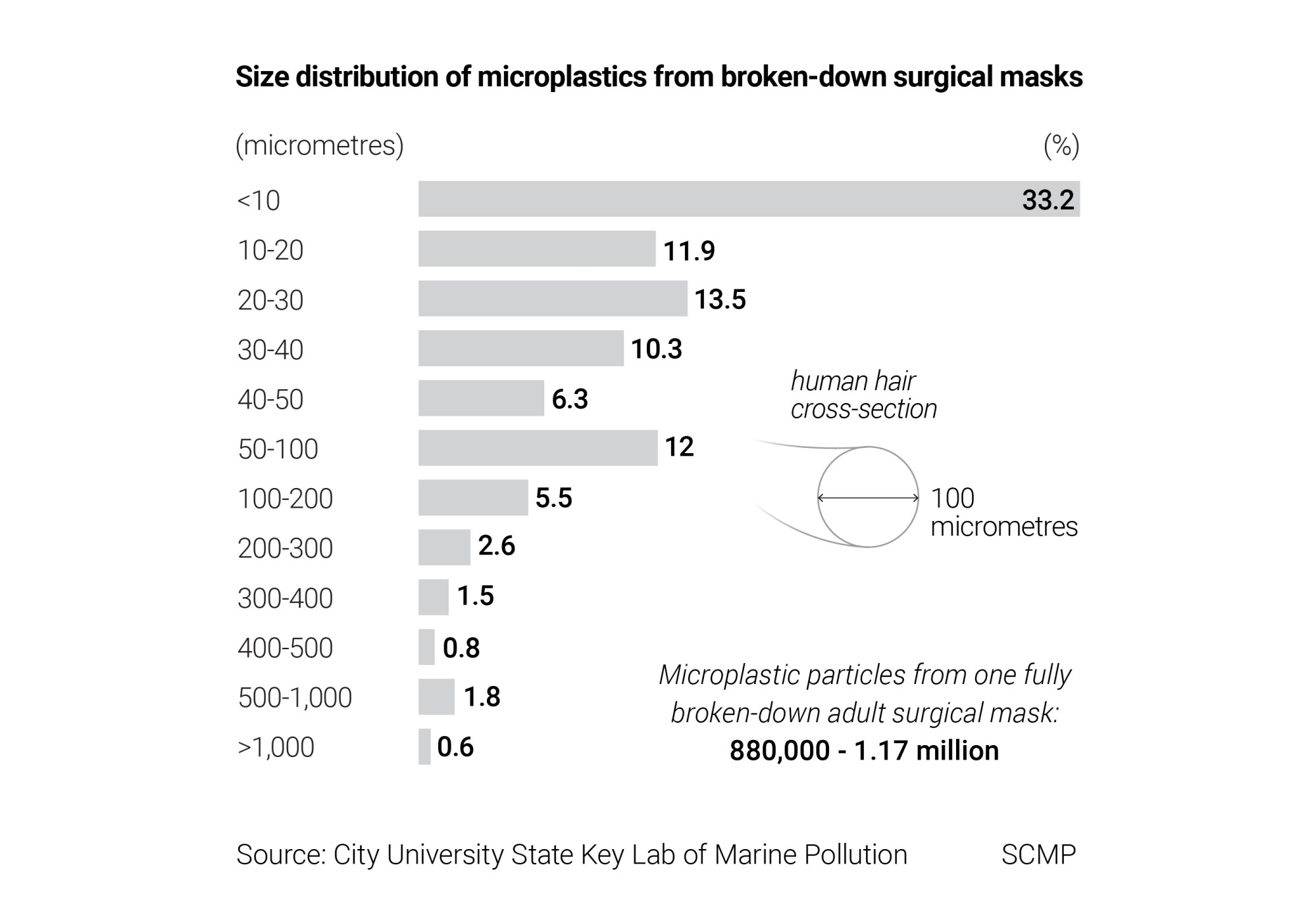

His lab study found that one mask, weighing between 3 and 4 grams, could fully break down into 880,000 to 1.17 million microplastic pieces after nine days, while already damaged ones could break down faster.

He said the figure could be an underestimate as they could not mimic sunlight.

A report by Hong Kong-based OceansAsia last year estimated that about 1.56 billion single-use surgical masks would have entered the sea in 2020. He estimated that this could lead to the release of 1,370 trillion pieces of microplastic.

At a concentration of 10 microplastics per ml of water, the CityU professor said the total amount would pollute a volume of seawater equal to 54,800 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

He found about one-third of the pieces were less than 10mm in size, while another 25 per cent of the fragments were bigger than 50mm.

These minuscule bits can be eaten by microscopic crustaceans called “copepods”, which are found in almost every saltwater and freshwater habitat, providing food for larger animals including fish and even whales.

He tested the impact on one species, Tigriopus japonicus, and found their reproductive abilities had been reduced by 22 per cent, while their nutrient intake and growth rate had also slowed.

How Hong Kong’s nastiest plastic pollutant hides in plain sight

The researchers said they were worried it could produce a domino effect on marine ecosystems, especially as masks were not the only source of microplastics in the ocean.

Microplastics from other waste, which can include drink bottles, cosmetics, clothing and fishing nets, are already extremely difficult to remove from the environment.

If the copepods were full from eating microplastics, they would end up eating fewer algae, leading to red tides, large blooms of aquatic plants which choke off oxygen in the water and kill other animals.

A reduction in the numbers of copepods because of slower reproduction could also spell decreased food sources for other species, He warned.

“Since the masks are a disease prevention tool, what we really need is stronger enforcement to prevent littering of the masks,” said Kenneth Leung Mei-yee, a professor who was also involved in the study.

In a response to the Post, the Environmental Protection Department said residents should not leave used face masks and “any other handy items” unattended when out in the countryside.

The department added it was using unmanned aircraft systems to monitor the city’s 1,200 metre seashore, which shortened the time required to survey 65 coastal sites in the Northern, Tai Po, Sai Kung, Sha Tin, Tuen Mun, Southern and Islands districts.